The Failed Impeachment of Gov. Bill Sheffield

(2019©donnliston.co)

|

| Governor Bill Sheffield grins as he walks back to the Capitol building in Juneau flanked by his attorneys John Conway and Philip Lacovara in 1985. (MICHAEL PENN / Anchorage Daily News) |

William Jefferson Sheffield was another father figure governor of Alaska. Elected in 1982, he was the executive for one term—until 1986—and the only one to be impeached.

Perhaps corruption in Alaska at this time was inevitable.

William Jefferson Clinton, the 42nd president of the United States, would be impeached in December, 1998. But the shadow of Richard Nixon’s impeachment August 9, 1974 hung over the Alaska event involving Sheffield.

Alaskans knew Sheffield in the old days as a bartender. By definition that means he helped some people self-medicate and provided uncertified counseling services. He became a successful hotel owner. Upon election as a bachelor he had a hot tub installed in the Governor’s Mansion.

On the bright side, in 1983 Gov. Sheffield initiated purchase of the 482-mile Alaska Railroad. President Ronald Reagan signed legislation authorizing transfer of the Alaska Railroad to the State of Alaska.

October 26, 1984: Governor Sheffield appointed the first Board of Directors of the Alaska Railroad Corporation. Board members in founding partner of Dowl Engineers), Myron Christy (retired CEO of Western Pacific Railroad Company), Gerald Valinske (member of United Transportation Union and Alaska Railroad employee), Richard Knapp (Commissioner of Transportation and Public Facilities), and Loren Lounsbury (Commissioner of Commerce and Economic Development). Frank Turpin was appointed the first President & CEO of this state-owned enterprise.

In 1985 the transfer of ownership of the Alaska Railroad took place. The State of Alaska purchased it from the Federal Government for $22.3 million.[1]

But Gov. Bill Sheffield Administration is not remembered much for that.

For background: Article II, Sect. 20 of the Alaska Constitution provides for all civil officers of the State to be subject to impeachment by the Alaska Legislature. Originating in the Senate, the motion for impeachment must be approved by a 2/3rds vote of the members. The trial must be held in the House of Representatives. Alaska’s senate has only 20 members.

A 1985 grand jury report alleged that this governor had attempted to steer a state office lease in Fairbanks to a political supporter and recommended that the legislature initiate impeachment proceedings against Sheffield. The legislature did convene a special session and began a hearing but there was no statutory implementation of this constitutional section. In Alaska’s constitution important preliminary questions were undefined, including whether impeachment was reviewable by the courts, argued the lawyers. They contrived a legal hole large enough to drive a locomotive through. In the end, the Senate Rules Committee which heard the evidence, did not find sufficient cause for the full senate and house to proceed with this legal exercise.[2]

One Senate committee saved Sheffield’s bacon.

That is the sanitized version of what happened, but there is more to this sleezy story.

I remember well in Juneau that the State of Alaska was experiencing high income from oil production in those days and everybody had a scheme to throw money at.

In his 1997 book Extreme Conditions, Pulitizer Prize winning journalist John Strohmeyer documents conditions from sudden oil wealth leading to big time Alaska political corruption.

The money is gone.

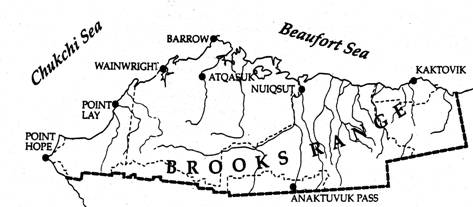

Strohmeyer’s story begins on the North Slope where Prudhoe Bay is located.

As the seat of the North Slope borough, which taxes all of the Prudhoe Bay oil fields, Barrow is the richest city, per capita, in the United States, and possibly in the world.In recent years it has also probably attracted the greatest number of unscrupulous people, per capita. That they have managed to extort many millions of dollars of Eskimo wealth is a scandal little known beyond Alaska.[3]

The North Slope Borough (NSB) was created in June 1972 by an essentially Eskimo election that voted for it 402-27. Alaska courts validated that election to establish the largest local government in the world with some 5,700 mostly Inupiat Eskimos residing in an area the size of Minnesota. Forming a local borough government was culture clash at its most extreme.

A desire by Barrow patriarch and first mayor Eben Hopson to bring Barrow into the modern age attracted many advisors to Barrow. He desired for the community to have all the amenities found in Anchorage or Fairbanks. Residents wanted running water and flush toilets, which required digging and building a utilidor. With their new wealth they believed they could have anything. But Hopson died in 1980.

The second NSB mayor, Eugene Brower was the former public works director under Hopson. His administration as mayor proceeded to borrow hundreds of millions of dollars—the debt swelled from $453 million to $1.2 billion over three years—by floating bonds backed by the NSB’s considerable oil property tax base. Legislation in Juneau to cap the run-away spending was proposed amid fears the state could be left holding the bag when oil revenues declined and the borough could no longer meet payments. The doors of corruption swung open.[4]

The vultures flock.

Former commissioner of labor under Gov. Bill Egan, Lew Dischner was now a lobbyist for several large clients, including the Teamsters Union–the most powerful labor group in the state. With a considerable network of influence Dischner had a reputation for delivering hefty campaign contributions to primarily Democrat candidates for public office. His efforts on behalf of Mayor Hopson resulted in Dischner becoming borough lobbyist and kingmaker–by engineering the election of Brower. We know now that some $100,000 for the campaign was laundered through a variety of people who contributed, but the money actually came from Dischner and a variety of contractors looking for NSB business.

Mayor Brower’s other confidant, Carl Mathisen had parlayed minimum previous experience in Anchorage contracting into a position as borough training program coordinator, where he had come to know Brower in the Public Works Department. Mathisen became Mayor Brower’s mentor in the ways of government. As consultant to the mayor and public works department, handling special works capital projects, Mathisen soon earned an average of $300,000 per year. Dischner and Matheson

teamed up and recruited a network of vendors who agreed to pay them a 10 percent kickback on any contracts received from NSB.

Accordingto Strohmeyer:

The consultants became the government, said Chris Mello, then contract reviewer for the borough. A California native, barely thirty years old and fresh out of California Western School of Law in San Diego, Mello was working at his first real job. He admits he was puzzled by what he saw at first, and then was simply dismayed. “In my first meeting with Lew Dischner, he told me he was a blood brother to the mayor, and what he said went,“ Mello says. “Suddenly the borough was starting hundreds of projects and running them was wrestled away from the borough employees and turned over to the consultants. We were reduced to clerks.”[5]

As costs for the growing number of construction projects awarded in no-bid contracts escalated, the people of the North Slope began to be concerned that their money was being siphoned to outside interests. The high school, originally projected to cost $25 million, soared to $80 million. The mayor’s lifestyle became lavish. And despite a $250,000 campaign fund raised with Dischner’s expertise, Brower was voted out of office in the fall of 1984. George Ahmaogak became mayor! And, during the last five days in office Brower’s administration pushed through more than $15 million in checks and signed $7.6 million in contracts.

A devastating subsequent audit by a Fairbanks accounting firm found wholesale fraud. While on the borough payroll as consultants Dischner and Mathisen had set up firms of their own to get borough business. Their company North Slope Constructors was able to shut out other firms by bidding low and then negotiating change orders.

“That substantially increased the size of the contract without substantially increasing work to be done,” the audit reports.[*]

As widespread North Slope Borough corruption became known, Gov. Sheffield was asked about it. When he replied that he was not aware that any state money had been involved, he was challenged by the fact that more than $4 million of state money had been budgeted for a half-dozen projects, questioned in the audit.

The plot thickened before our eyes

Dischner had been one of Sheffield’s largest contributors in his campaign for governor. By spring of 1985 the Fairbanks News-Miner proposed there may be something amiss about a 10-year, $9.1 million lease the state had signed for office space in a certain Fairbanks building. Specifications for the bid had been written so narrowly that only the one building had qualified.

Strohmeyer: Stan Jones, a reporter on the News-Miner, dropped the Barrow story and plunged into a round-the-clock investigation of the Fairbanks lease. He reported that a labor leader named Lennie Arsenault, who had helped raise $92,000 for Sheffield’s campaign, had a financial interest in the favored building. Further, he found that Arsenault had had discussions with the governor regarding the lease and that employees within the state leasing office had protested the circumvention of leasing procedures.[6]

State prosecutor Dan Hickey impounded all leasing records in the procurement office and launched a grand-jury investigation of the governor. Sheffield made two appearances before that grand jury. Alaska attorney general Norm Gorsuch responded to Hickey’s discovery by recruiting a special prosecutor from Washington D.C., George Frampton, who had worked as a special prosecutor with the Watergate grand jury in the impeachment inquiry of Richard Nixon.

The Alaska grand jury worked for ten weeks, calling in more than forty witnesses and preparing 161 exhibits as it built a case against Sheffield.

Again, as reported by Strohmeyer:

On July 2, 1985, the grand jury returned a devastating report. It charged “a serious abuse of office” by Governor Sheffield and his chief of staff, John Shively, in their alleged intervention into the lease process and in their attempt to frustrate official investigations into the matter. Inspired, according to some, by the climate of the Watergate hearings, the jurors called Sheffield unfit to hold office and recommended the senate be called into special session to consider impeaching the governor.[7]

Republican President Nixon had resigned August 9, 1974 when facing certain impeachment and removal from office for the Watergate break-in. Democrat Sheffield fought it.

Sticking by his story–that he didn’t remember meeting with Arsenault–Sheffield further argued that consolidating state offices in Fairbanks would save money. Shortly after the grand jury report Attorney General Gorsuch–who had been appointed to that position by Sheffield, issued a legal opinion–stating that the administration should cancel the lease because it was tainted by favoritism–and immediately resigned. Sheffield quickly then appointed Ketchikan attorney, Hal Brown, who fired prosecutor Hickey as his subordinate in the Alaska Department of Law.

A nagging question: Should Alaskans elect their attorney general as many other states do or should the top law official serve at the pleasure of the governor?

As might be expected given the players, the Alaska Senate Rules Committee impeachment debate resembled Watergate. Republicans were in the majority 11-9 in the senate and former Watergate committee counsel Sam Dash was brought in to oversee the proceedings. For his defense, Sheffield hired Philip Lacovara, counsel to Watergate prosecutor Leon Jaworski.

Dash argued that Sheffield’s tampering with state leasing procedures might not amount to an impeachable offense, but perjury would. This is the same “perjury trap” Americans have become familiar with in recent national political events surrounding election of Donald Trump as president: Sheffield had testified under oath four times that he could not remember ever meeting with Arsenault, while not only Arsenault but also Chief of Staff Shively told the grand jury in detail about a meeting in which the governor and Arsenault discussed lease specifications.

Bumpkins in the Alaska Senate not only rejected Dash’s case for impeachment but also gutted a subsequent rules committee resolution denouncing Sheffield for questionable veracity and “significant irregularities.” Instead they called for a study into state procurement procedures and added a resolution recommending the Alaska Judicial Council “study the use of the power of the grand jury to investigate and make recommendations…to prevent abuse and assure basic

fairness.” Five years later Sheffield was further rewarded in a catchall bill–ostensibly to fund the state’s longevity bonuses and legal expenses to recover disputed royalty payments from oil companies–which included a payment of $302,653 for Sheffield’s impeachment legal fees.

Dishner and Mathisen were prosecuted and on May 23, 1989 a federal jury found Dishner, now 73, and Mathisen, now 57 guilty of more than 20 counts each of racketeering, fraud, bribery and accepting kickbacks from contractors. U.S. district judge James M. Fitzgerald sentenced each man to seven years in federal prison and ordered them to forfeit more than $5 million in property.

As a frog jumps from Lilypad to pad, after leaving the position of Governor, Sheffield served as Chairman of the Alaska ‘Railroad Board of Directors from 1985 to 1997. In 1997 he was promoted to President and CEO of the railroad, where he served until 2001.

At age 91 Sheffield was removed from his director’s seat and named Alaska Railroad Board Member Emeritus in November of 2019 by Gov. Michael Dunleavy.

But back in In 2003 Sheffield had been named Director of the Port of Anchorage by Mayor Mark Begich. Another disaster ensued. In 2013 Sheffield resigned after working at the port for 10 years and being the public face of an ambitious expansion effort that had ended up way behind schedule and far over budget.

The port is owned and operated by the Municipality of Anchorage. To date, the project has received $439 million. The State of Alaska has contributed nearly $220 million, federal government has given nearly $139 million and the port has added more than $80 million in loans and tariff generated revenue.[8]

But now everything is tied up in court, we are years away from completion of the re-engineered dock upgrade, and Alaskans can be sure it is going to be expensive.

Uncle Bill Sheffield doesn’t do things on the cheap, you know.

References:

[1]Alaska Railroad History

https://www.backcountrysafaris.com/alaska-railroad/railroad-history.php

[2]Harrison, Gordon S., Alaska’s Constitution; a citizen’s guide, Alaska Legislative Affairs

Agency, 2002 S

[3]Strohmeyer, John, Extreme Conditions, Big Oil and the Transformation of Alaska, Cascade Press, 6633 Lunar Dr., Anchorage, AK 99504, 1997, p123.

[4]Ibid, p124

[5]Ibid, p 127

[6\Ibid p 130

[7]Ibid p 131

[8]Ibid p 133