How Can Alaska Gain True Food Security?

This updated story was first published June 5, 2020

Alaskan grown beef prepared for market at Mt. McKinley Meats & Sausages.

Alaskans know when calamity strikes we can expect to see responding events happen fast. The November 2018 earthquake was such a wake up call–and the pandemic of 2020 further drove the fact home:

We in Alaska are not food secure

Some individuals may be food secure–due to special efforts–but an estimated $3 Billion worth of beef, pork

and chicken are shipped to Alaska for food consumption every year, according to Greg Giannulis, who has owned and operated Mike’s Quality Meats in Eagle River now 32 years.

When I bought the business I couldn’t afford to change the sign so I kept it as Mike’s Meats, Giannulis joked from behind his desk at 12110 Business Park Blvd. in Eagle River.

I met with Giannulis for this interview the last Saturday in May while he was also running things between answering my questions. A brusk Greek Immigrant, Giannulis told me he started his Alaska adventure buying lambs and butchering them as specialty meats. He had worked in a slaughterhouse and was trained in the old

country. Today he owns the original storefront retail meat store, with warehouse nearby, Rocket Ranch in Palmer, and for more than three years the USDA certified Mt. McKinley Meats and Sausage (MMMS) plant in the industrial park near the Palmer Fairgrounds. This is the only USDA meat processing plant in Southcentral Alaska and Giannulis bought it out of necessity.

|

| The child of an employee greeted us at the main office of Mt. McKinley Meat and Sausage on a Saturday visit of the facility |

Q: As a meat retailer you already used Mt McKinley Meats as your slaughterhouse?

A: Yes, they were my slaughterhouse. So, one day I called down there and told them I have two loads of beef, 80 beef I need processed. They replied: “No way in hell can we do it!” The following week I needed some pigs processed and they said “We cannot take five pigs for two or three weeks.”

Q: So you had to pay to maintain those animals over that time?

A: Yes, they were costing me money. So I got mad; I don’t need another business, I’ve got enough to do, but you play with my money and I will do something. They kept telling me they will prioritize my needs but it was all double-talk. Five valley farmers were trying to buy the plant but they cannot even raise a $10,000 deposit to make an offer between them!

Once awarded the bid, Giannulis paid for the plant with a cashier’s check for the full amount; $300,000. He says he has put two times that much into upgrading it to standards he has always maintained for his products. He credits his team of managers for being successful over the many years.

And, MMMS has made a profit every year since the State of Alaska (SOA) was finally able to divest itself of

this government-run money pit.

Imagine that!

The enterprise owned by Giannulis provided a safety net.

With the Earthquake (of November 2018) the shelves of local stores were empty for a

week or two! Giannulis reflected. Now with the pandemic, meat is essential and nobody has enough. The supermarkets even limit how much you can buy, he continued. So, I am the only place you can buy as much

meat as you want directly available; Mikes Meats, Valley Meats in Wasilla, Echo Lake Lockers in Kenai, Carr-Gottstein and Three Bears, because I have a processing plant–which is essential to Alaska Food

Security.

He continued: When the pandemic was announced, suddenly nobody had meat. I closed because I didn’t want customers coming in and out, but I had meat for Alaskans.

In fact, Giannulis continues: Within 30 days after the pandemic hit I slaughtered every available animal in Alaska. They gathered them up and I got them all processed. I also pulled beef from Washington, I pulled from Canada; I received a truckload last Monday, beautiful beefs, and I have them processed already on Saturday, and the plant is totally clean and ready for next week. I have a few here now and another truckload coming next week—30 or 40 of them.

|

A child stands on the ramp inside of the huge trailer used to bring livestock to Mt. McKinley Meat and Sausage for processing. 40-45 live steers can be transported by this method.

|

This is Commercial Agriculture and

it is what Alaska must

pursue for food security.

Meaningful Food Security

A former Alaska Division of Agriculture Asset Manager, Ray Nix witnessed the failed efforts of the SOA to make the slaughterhouse viable over his career. In retirement now, Nix continues to be a trusted advisor to Giannulis, and joined our discussion: Greg needed to control his own destiny, Nix clarified. Adding a slaughterhouse assured processing of animals for his retail business. When it was operated by the State he had no control over production levels. He couldn’t go after additional markets if they wouldn’t kill his animals. So, he got plans and was looking to build a slaughterhouse, when he was approached about the potential of buying this facility.

Nix: There were some negotiations between Greg and the State, and there was a lot of investment that had to be done to this facility, and Greg made a cash offer. It had to be done correctly for the State to transfer ownership, and ultimately Gov. Bill Walker said: “You need to privatize it. It isn’t going to be open, it isn’t going to be funded, you need to privatize it.”

In December of 2016 the next offer by Greg was accepted. He took possession in May, 2017.

Nix continued: Keep in mind–that place had been offered so many times, when I was employed at the Division of Agriculture doing the offerings, it was obvious that for that facility to work it had to go to somebody with the background and capital to not just pay the utilities—because that was expense enough—but to pay for the operating expenses. Nobody would propose to do that—if you spent a

lot of money to purchase the plant you would need to have the additional amounts available for operation to make it viable.

The primary purpose to privatize was to 1. Get the state out of the business because they weren’t running it effectively, and 2. Maintain the USDA stamp for Southcentral Alaska—that is the key to growth of agriculture in Alaska, according to Nix.

Another Likely SOA Boondoggle

We who have witnessed the State of Alaska go from being a broke new state on the federal teat, to rich beyond our imaginations from the single resource of oil, have also noted the many investment boondoggles endured. Most were agricultural pie-in-the-sky failures. So it isn’t too much of a reach to see that this one

was headed to the same place from its similar origins as a good idea proposed by people with good intentions.

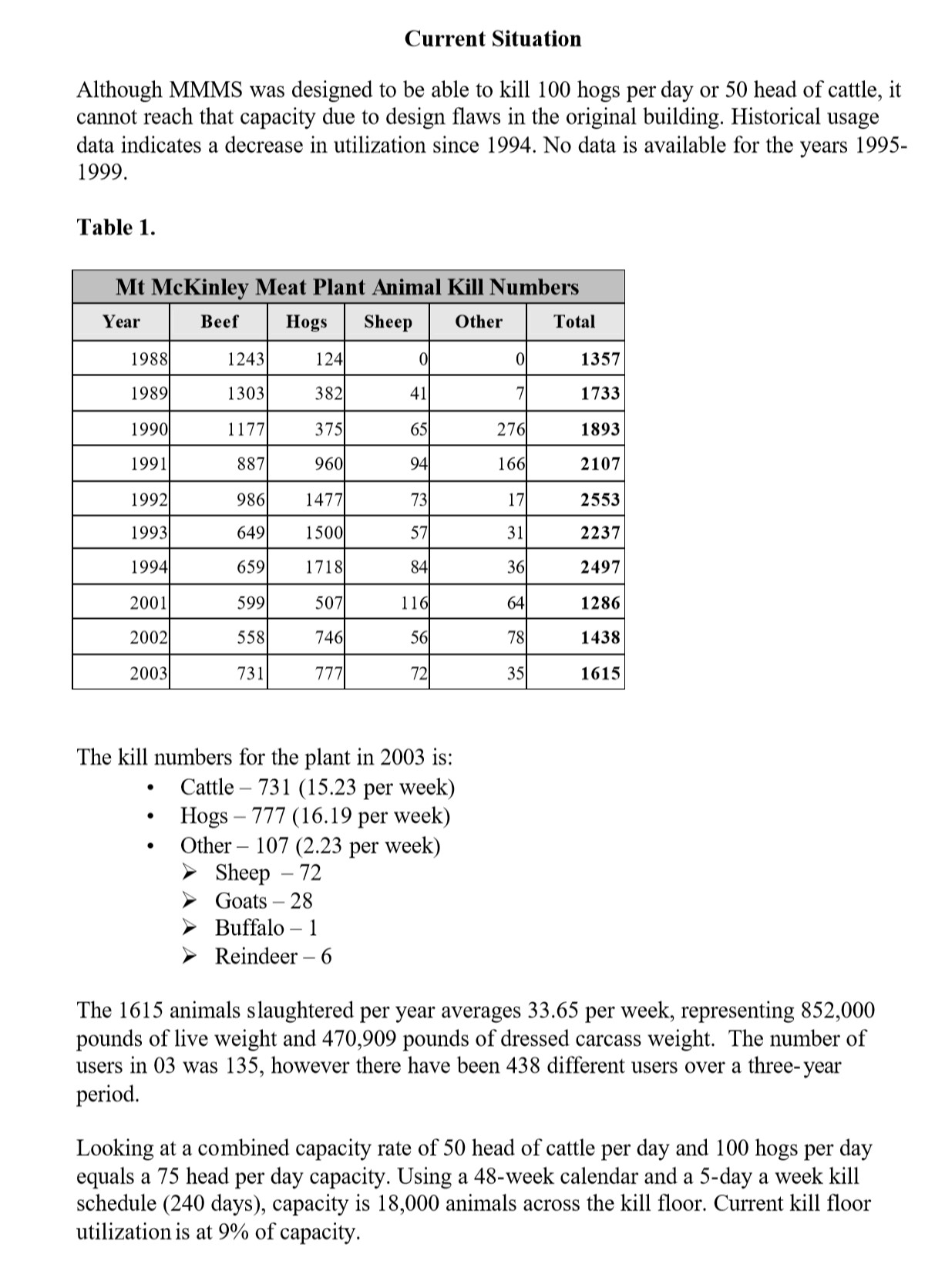

A 2003 study by the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, Division of Agriculture, examined this state-owned slaughterhouse and what might save it.

[1]Mt. McKinley Meats and Sausage Review and Recommendations Final Report 2003

A Business Planning Team, led by John Torgerson, Acting Director for the Division of Agriculture, and including staff members Marian Romano-Development Specialist, Melanie Trost-Development Specialist, Ed Arobio-Natural Resource Manager, and Dennis Wheeler-Attorney, resulted in a final report produced by Romano and Trost. The Team used data currently available from staff and stakeholders and research previously completed. Some primary research was conducted. This Team analyzed all the available data and made recommendations to the Director for each issue addressed.

From that report:

Historical

Perspective

The Mt McKinley Meat and Sausage Company (MMMS) was originally constructed as part of an ambitious plan to radically expand agriculture through state supported infrastructure development in the late 70’s and early 80’s. It was financed with $2 million of Agricultural Revolving Loan Fund (ARLF) monies in 1983 and then further financed with private funds of $1.2 million, to support cashflow.

A combination of factors, including an economic downturn predicated by reduced oil prices, a precipitous drop in grain prices, and a change of administration brought about the abandonment of the concept of agricultural infrastructure expansion by Gov. Steve Cowper. Many projects were abandoned, such as the grain elevator in Seward and the slaughterhouse facility in Fairbanks. Dairy farms went into foreclosure, as did the MMMS. The ARLF, in second position to the private lender, purchased the asset in a foreclosure sale in 1985 at the end of the Administration of Gov. Bill Sheffield.

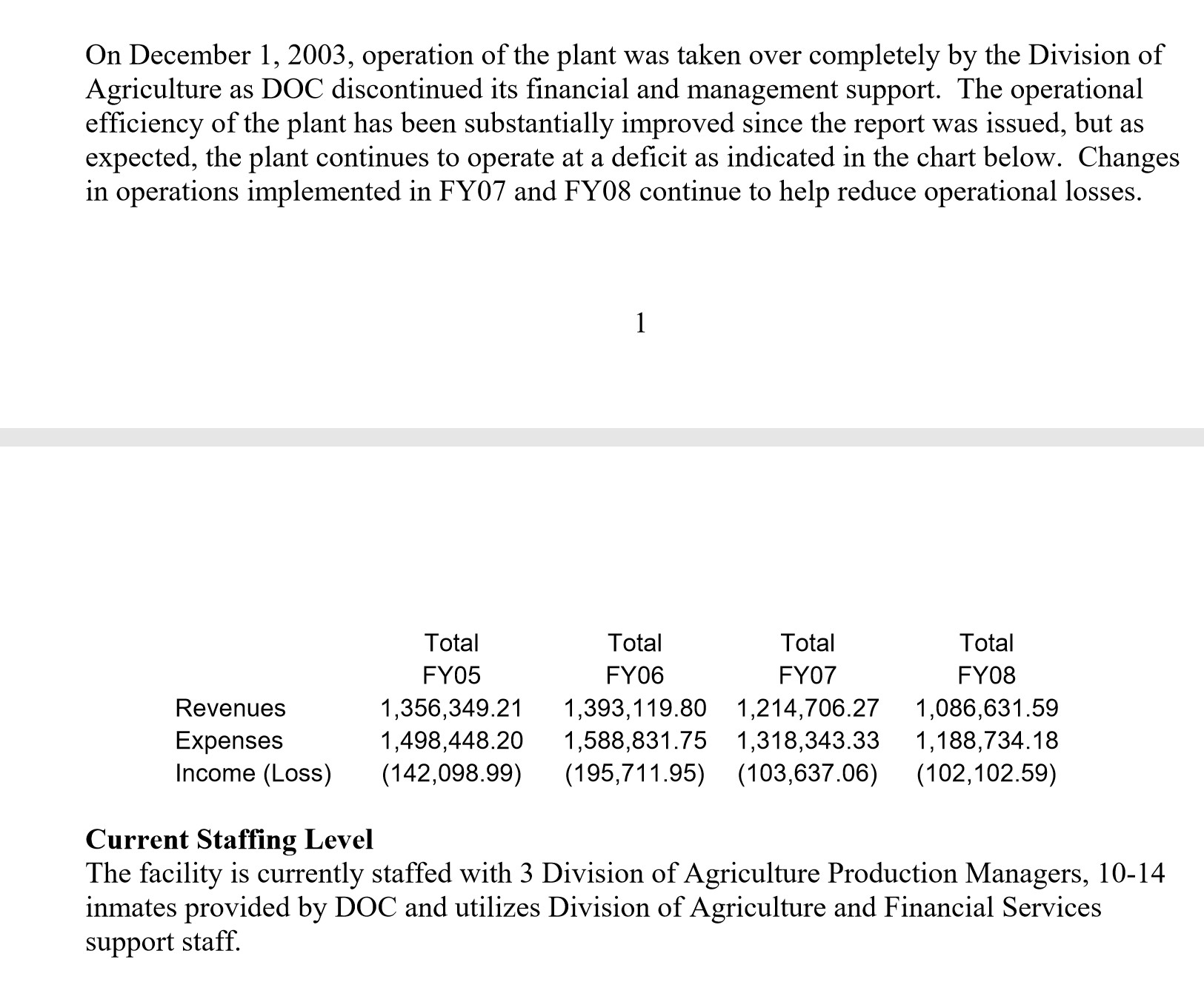

Once the SOA abandoned “agricultural infrastructure expansion” Alaska farmers were on their own with the Division of Agriculture doing a lot of hand-wringing. Further, this is how SOA bureaucrats envisioned in that report the future of an uneconomic MMMS subsidized by SOA:

The plant remained closed for several months, then was reopened in 1987 in conjunction with Department of

Corrections (DOC), Alaska Correctional Industries (ACI) as a training and rehabilitation facility. The plant has operated under this scenario since then, with the original intention to transition it into private hands. Several attempts to lease the facility have been unsuccessful.

Over time, in an effort to reach break-even status, the plant has regained its USDA inspection status,

added custom cut and wrap services, counted on the settlement of Mental Health Trust lands to increase livestock production, began selling to institutions, purchased boxed meats to augment those sales, and intervened to prevent private sellers from selling products at distressed rates that undercut MMMS prices to

institutions. Each of these action steps was intended to be the solution to the problem of operating losses; none were.

MMMS has traditionally not met its operating expenses, not including DOC and ACI staff, until FY 2003. In FY 2003 and 2004, as the result of budget cuts, the Commissioner of DOC asked the Director of Agriculture to reimburse the cost of ACI and DOC staff as well as operating shortfalls. As a result of these new costs to the shrinking ARLF, from which monies come to support both the Division of Agriculture and MMMS, the Director has decided to look at alternative operating options for the

plant.

As a result of this quest for other options, the following information has been gathered in order to have

accurate, current data upon which to base future decisions.

A look back at various public hearings and Board of Agriculture meetings finds a series of common solutions

that come to the forefront at each meeting. Recurring and persistent recommendations for success of the MMMS plant have been:

• Increased hog production

• A co-op to operate the facility

• A private person to operate the facility

• Diversification of the plant

These researchers in 2003 found there was no record of MMMS production levels for five years:

Still the asset of the State continued to lose in excess of $100,000/year as documented in a white paper written by Nix:

[2]

What Alaska must do for Food Security

Giannulis was processing an estimated 100-150 animals per week. He brings them from anyplace he can get them, using his own truck and trailers. He buys from 97 sources Outside that supply him through Seattle. There are not enough cattle being raised in Alaska to keep him in business for more than

one month.

|

| Each animal is humanly dispatched and attached to a hoist which raises each carcass for transport to each station of the process. |

Giannulis: We need more cattle to be raised in Alaska. A billion and a half per year is being spent outside just for beef.

Nix: That means more acres of land available. We need to have the Alaska Department of Natural Resources provide grazing lands with Ag Rights only. You cannot sell it, you cannot develop it, you can only graze domestic animals on it. From the Division of Ag we knew we have very limited Ag land available. There is a piece up north–about 125,000 acres–some out at Fish Creek and other scattered spots, but it’s not the best ag land and it isn’t being utilized. Bridges need to be built. Ag land is a tremendously costly part, getting it ready for use—even grazing—is expensive. So for sustainability DNR needs to authorize land for agriculture purposes.

Giannulis: What they offer now is 600-acre parcels. That doesn’t mean anything; you need 4-5 acres per animal, so how many animals can you raise on 600 acres? We need 20,000. 30,000, 50,000 acres for viability as Commercial Agriculture.

This isn’t Pie-in-the sky: He has studied how the

Canadian agriculture program works.

Mostly we need State policy that will allow us to feed ourselves, continued Giannulis. I have traveled to

Canada five times and spent a week each time to see how their agriculture business works. The smallest farm is 10,000 acres. They have 30,000, 50,000, 100,000 acre farms raising animals for meat. They produce anything and they make a lot of money because they don’t have the BS that farmers suffer with from the

government here. They raise a lot of animals and we bring some of them here for processing.

Alaskans are due to break our oil dependency problem sometime soon, as with the Gold Rush of the early 1900s, this state will again be home for people living here for the long haul. Perhaps now is the time for Alaskans to return to the basics of living the Alaskan lifestyle with food security, as we once did.

[3]

Gov. Mike Dunleavy was Senator from the Mat-Su agriculture zone and understands this, but what are the chances of policy improvements for Alaska food security coming from legislators in the government town of Juneau?

Resources:

1. Mt. McKinley Meats and Sausage Review and Recommendations Final Report 2003

http://www.dnr.state.ak.us/ag/MMMS/MMMSReviewandRecommendationsFinalReport120103.pdf

2. AK Division of Agriculture White Paper February 17, 2009

dnr.alaska.gov/ag/MMMS/MMMSWhitePaperFINAL02172009.pdf

3 Alaska Farm Bureau RE: Mt McKinley Meats, October 9, 2015

http://dnr.alaska.gov/ag/BAC/AKFARMBUREAUMMMS.pdf

Contact me at Donn@DonnListon.net

totally believe in food security. Get big gov out of the business and let people work and sell their products. good article.

Do not get tied up with global gov, esg, or carbon credit crap.

waynette