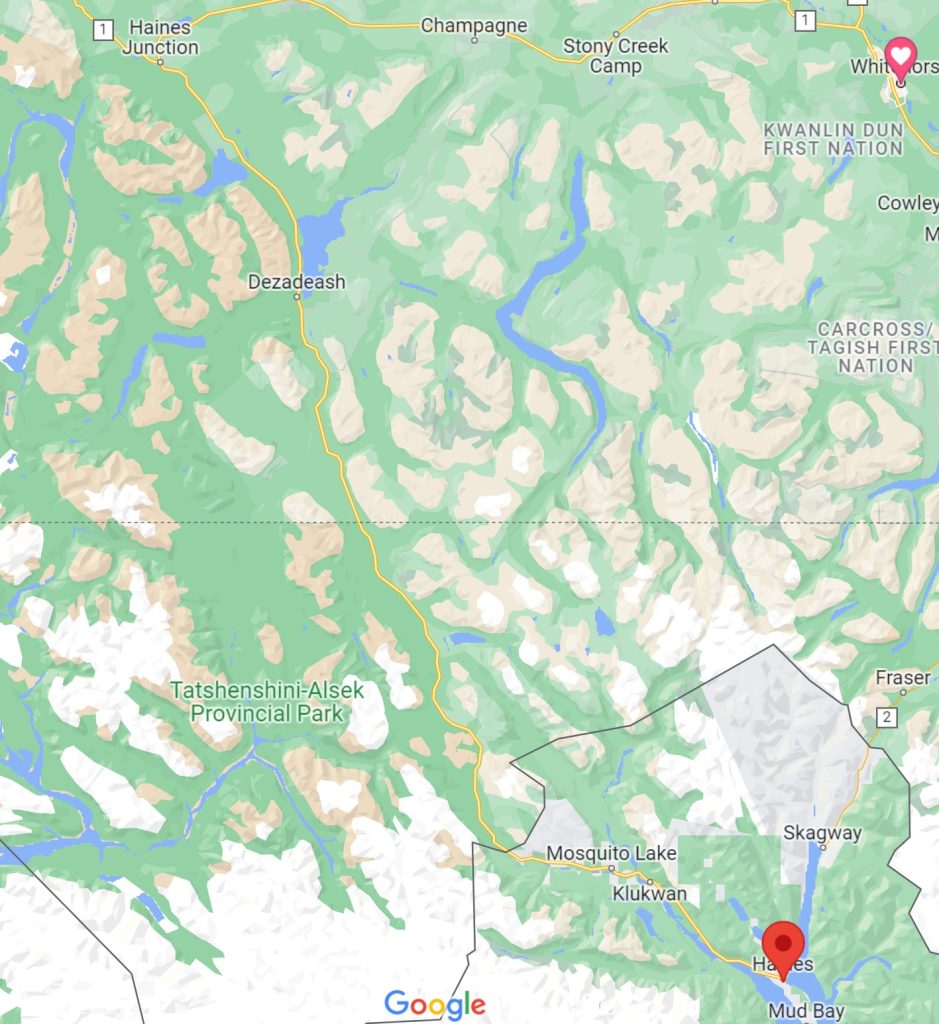

Alaska food security means different things to people in various regions of Alaska. When this writer lived in Southeast Alaska my freezer was filled every summer with fish and deer, but I was not so keen on spending a lot of time foraging for berries. In speaking recently with a food security advocate who lives at the end of the Haines Highway,[1] I discovered some other angles on the food security paradigm.

A trained chef, graduated from Culinary Institute of America in 1985, Brenda Josephson has spent most of her career in accounting and business management. Recently she returned to college to take an on-line Food Business Leadership program at her alma mater–motivated by an interest in learning new ways to address food sustainability and food security in Alaska.

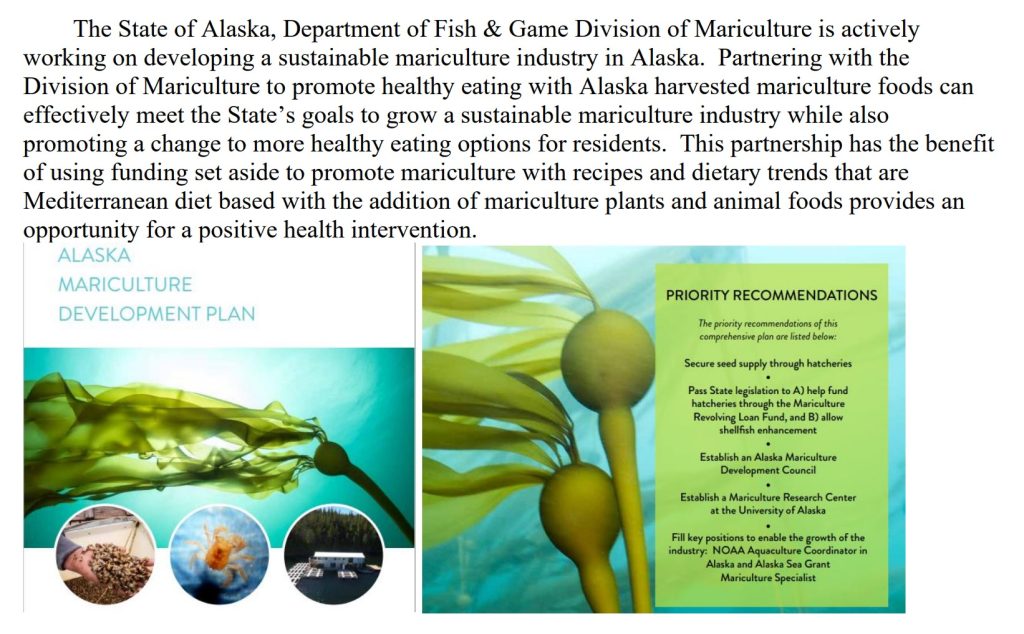

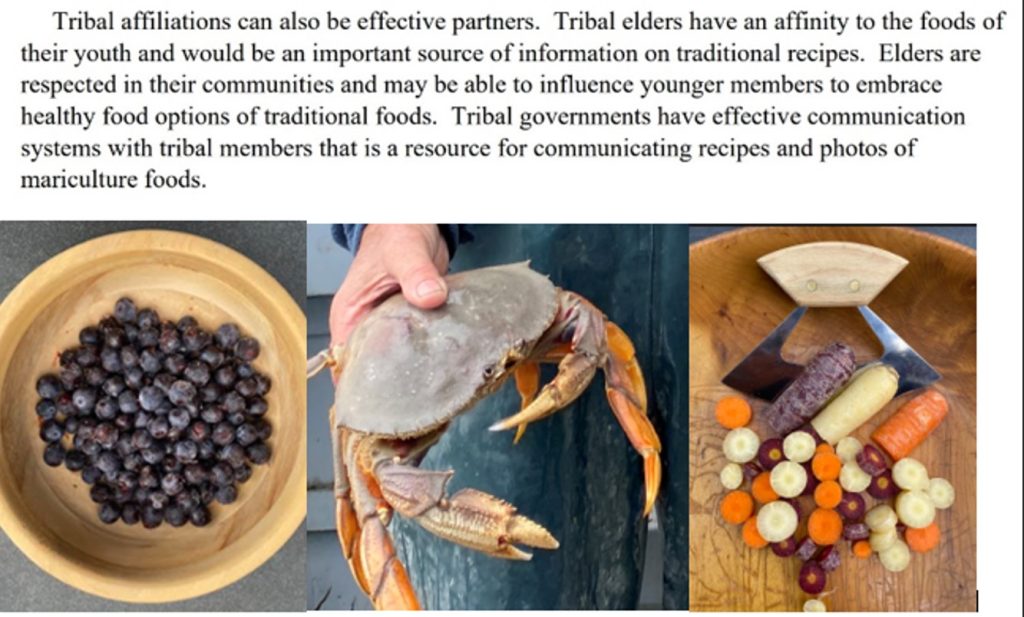

She is particularly interested in Mariculture–a specialized branch of agriculture involving the cultivation of marine organisms for food.

I believe we can achieve greater food security by doing some things differently, explained Josephson. The government has a role in messaging, but I do not believe this issue can be solved by the government and I do not support the government buying stock piles of foods, sending money to nonprofits to grow gardens, or any other of the boondoggles I have heard promoted to spend public resources in the name of food security.

A press release from the Alaska Division of Agriculture in early 2021 explained that the 2018 federal Farm Bill authorized the State of Alaska to issue micro-grants to support innovative ways to improve Alaska’s food security. The division began accepting scoping applications for three-year grants of up to $15,000 for individuals, or $30,000 for qualified organizations. The U.S. Division of Agriculture was set to provide $1.8 million to the division in each of the program’s first two years.[2]

You mean federal pass-through mini grants aren’t enough?

I’m going to be critical here about these grants to nonprofits; it’s not sustainable. It’s not going to bring food sustainability for us, said Josephson. I ask: What’s the end game when you no longer fund that nonprofit? When they don’t get the money one year will there be a garden that year? I don’t see this as being long term sustainable, because when the grant money runs out, they’re going to stop growing the gardens when they’re not being paid to do it. So that’s why I really think changing people’s desires for regional foods is more realistic–finding naturally available foods.

One organization Josephson does favor is the Alaska Fisheries Development Foundation, Inc. AFDF’s mission is to identify common opportunities in the Alaska seafood industry and to develop efficient, sustainable outcomes that provide benefits to the economy, environment and communities. Toward this end AFDF funds research in the categories of bycatch reduction, byproduct development, 100% utilization, (fishing) gear modifications, energy efficiency, and mariculture development. One of AFDF’s objectives is to share the valuable information produced through its work with interested parties. [3]

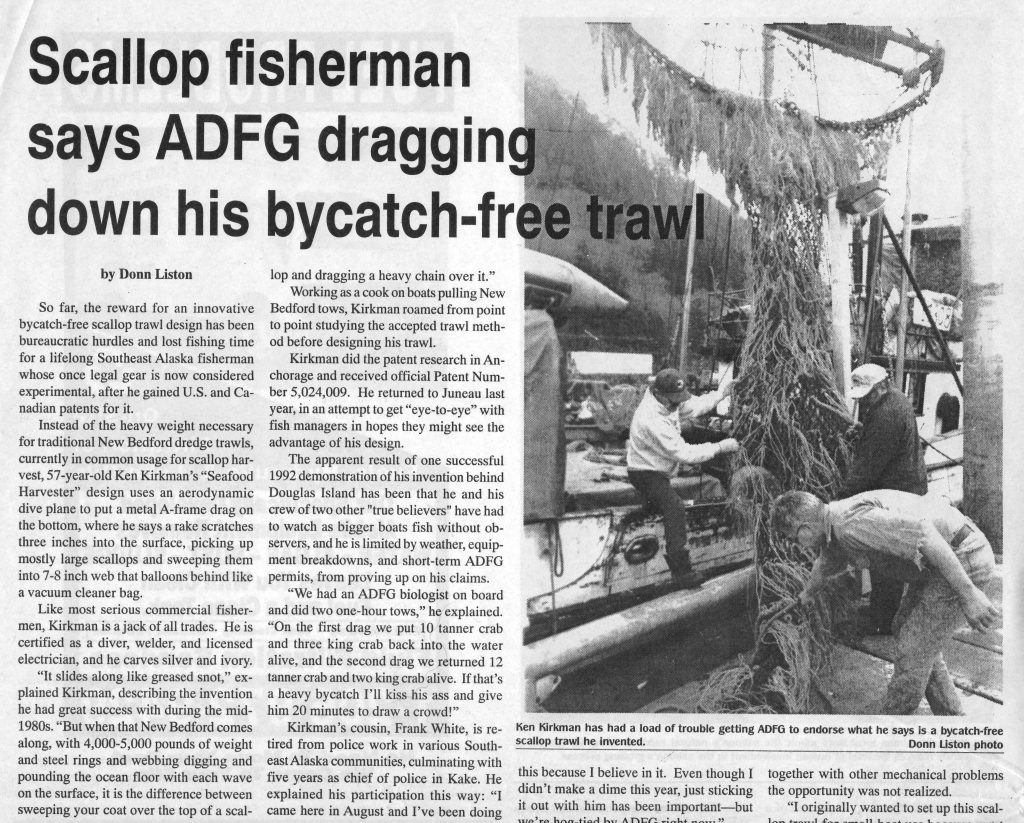

During the mid-1990s I wrote for a Seattle publication called Fishermen’s News which was started by the powerful commercial fishermen’s organization, United Fishermen of Alaska (UFA). That publication is today owned by a Maritime Publishing in San Diego, CA.[4] One story I wrote in March, 1994 was about an innovative bycatch-free trawl designed by a Juneau fisherman who was getting the run-around everybody still gets from the Alaska Department of Fish & Game.[5]

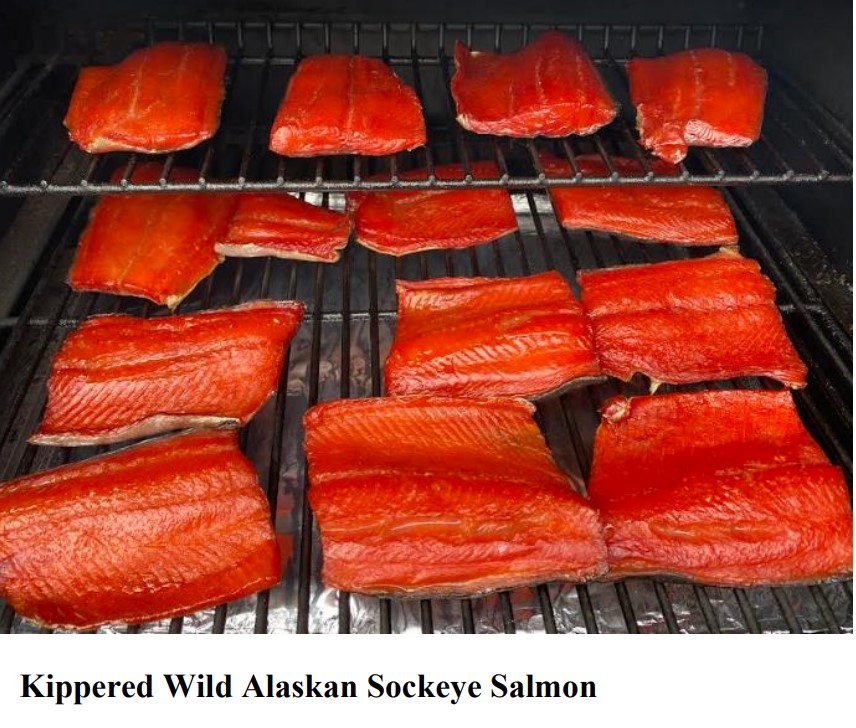

Alaskans in Southeast are also familiar with efforts to promote Alaska seafood through the Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute (ASMI), a public-private partnership intended to foster economic development for the mostly Outside-based commercial fishing industry.[6] ASMI provides seafood recipes for preparation of seafood delicacies from Alaska waters.[7]

Similarly, AFDE sponsors the Alaska Symphony of Seafood contest in Juneau, where our elected officials are often treated to spectacular seafood “receptions” sponsored by commercial fishing interests, which I have myself enjoyed immensely.

But make no mistake about it, our Alaska seafood bounty is owned by west coast producers who send boats from Washington, Oregon and California to scoop up fish and crab of all varieties for world markets. So, the idea of having an Alaska natural food contest might have some appeal among those who truly want to promote food security for Alaskans. Most of the commercial fleet couldn’t care less if Alaskans live or die.

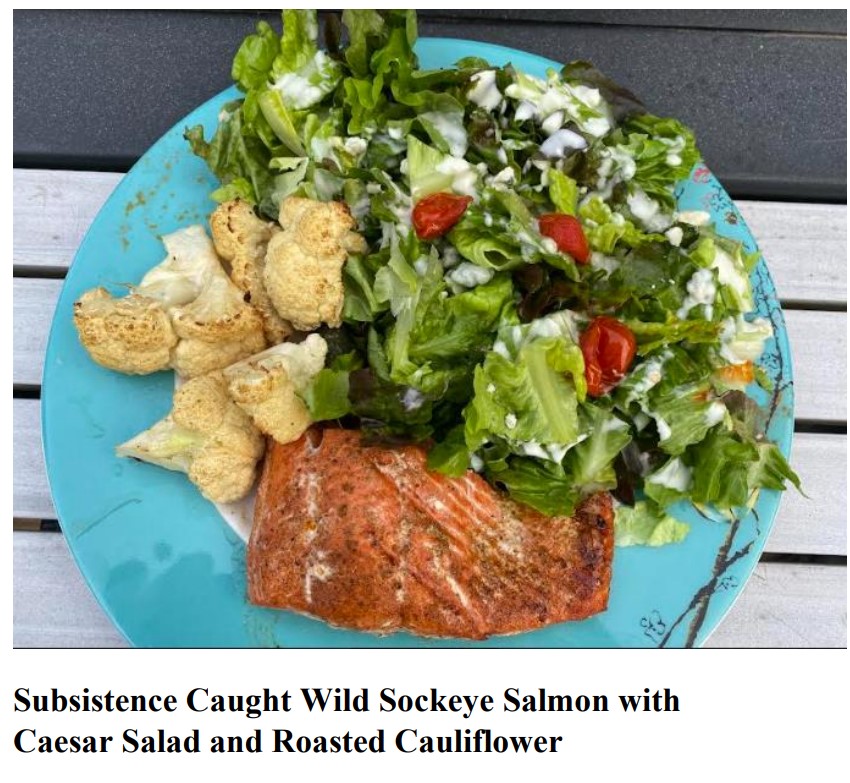

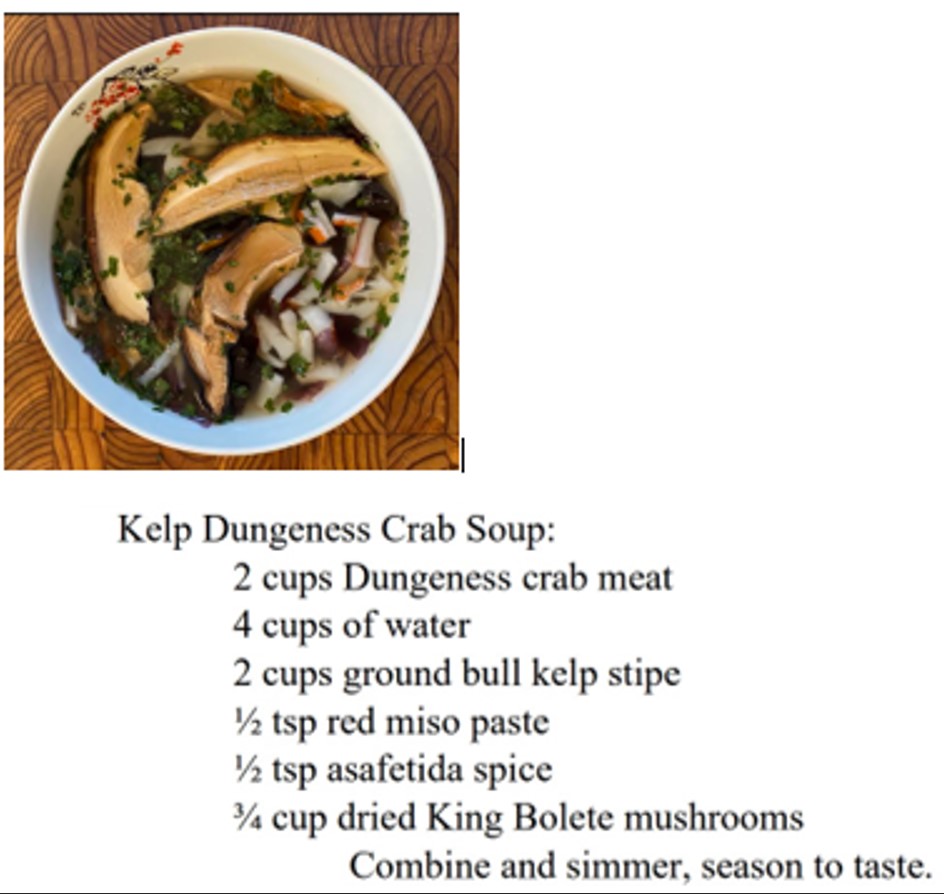

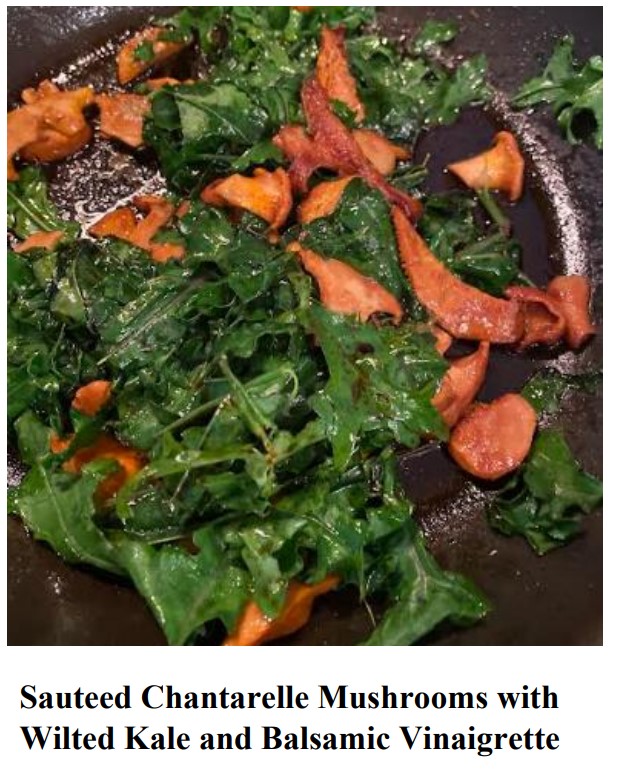

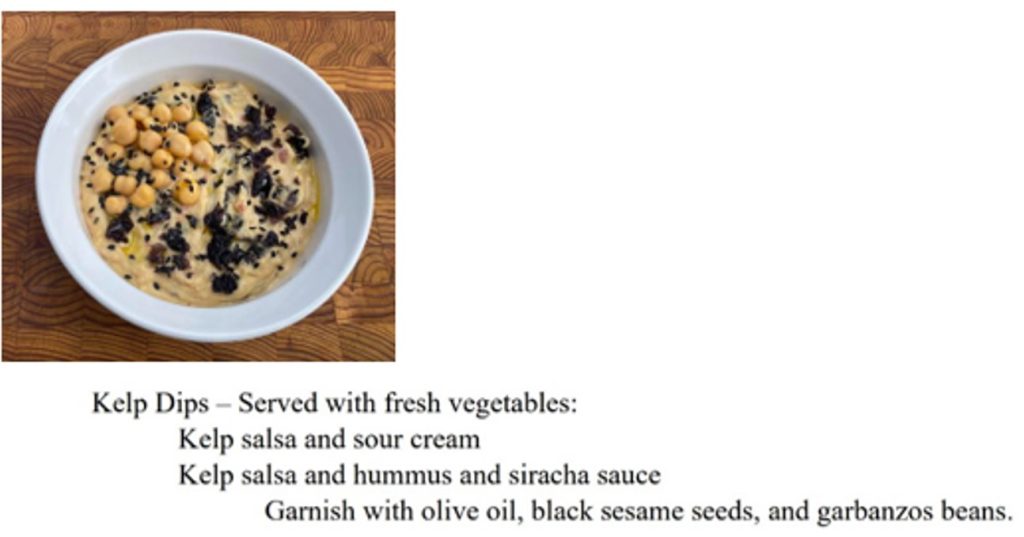

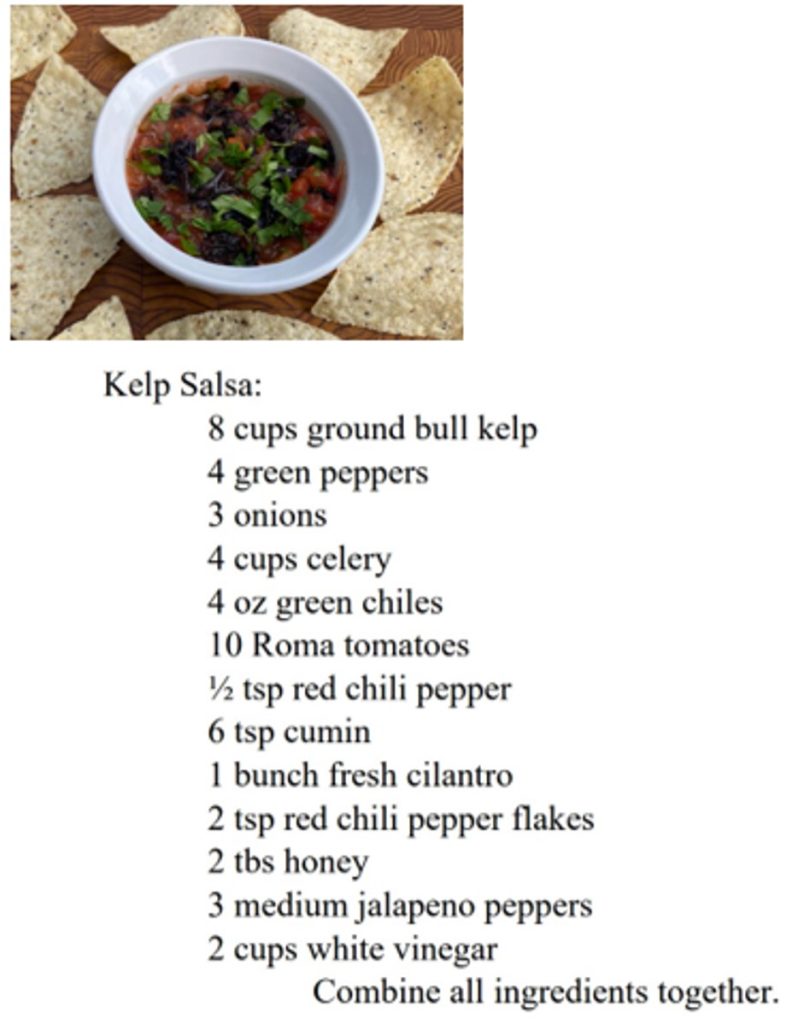

Josephson offers some recipes to begin the discussion!

Supply and demand rule.

We are tied to Seattle in other ways, too: Initially, I thought maybe I could do hydroponics commercially, Josephson continued, I considered purchasing a hydroponic trailer. But when I did the market research, I found out that everyone thinks it’s a great idea, but they are not going to pay more than what they pay for barged produce. I settled on purchasing a small hydroponic unit with the intention to sell herbs here in Haines.

So, what we’re really talking about, is getting people to change old eating habits to adopt new ideas of the kinds of foods that they’d like to eat, said Josephson, not because they have to do it–because they’re told this is not sustainable—but because they choose to for the enjoyable flavors. As a cook I have learned to enjoy the flavors and textures when I experience the fresh regional foods.

There’s a couple of weeks in the spring that I’m pretty excited to get fiddlehead ferns and they are available even up in the Anchorage area.

Eating natural foods is part of the Southeast Alaska culture. This writer had students bring dried smelt to eat like candy in my class when I taught 6th grade in Haines, 2006-07. Fiddlehead Restaurant and Bakery in Juneau is a popular establishment celebrating healthy natural foods, too.

Kelp farming is becoming a new niche of the food production paradigm.[8]

In Southeast Alaska, in the wet meridian temperate zone, we have a lot of fungi and a lot of berries. Southcentral has a lot of edible plants also, said Josephson. We need to consider what are we uniquely situated for in our local area rather than a morphing other agricultural foods that don’t grow well here. For instance, corn can’t grow here because we don’t have enough warmth, but we do have productive gardens from our abundant light. So, we can grow spinach and lettuces love our climate. Sometimes peas do well, sometimes they don’t. Alaska has barley. We have done it with some crops. We are importing chicken food and food for cattle–can we grow that? Will we ever get the land needed to grass feed cattle for a beef industry?

Josephson continued: There’s a lot of nutrition that we’re just looking past, because our food system has been so industrialized, and we concentrate on the industrialized food regime to provide for us instead of what is available naturally regionally. We must rethink what are we eating and why? What can we eat that is available here in Alaska?

What about our Alaska supply-chain issue?

We read about supply chain issues in the news every day, continued Josephson. I’m concerned about that, my family raises chickens, and we have plenty of eggs. Sometimes we give eggs to other people in exchange for donation toward feed. And there’s been times where we were the resource in the town for some because there are no eggs in the grocery store. I have pictures of it; no dairy and no eggs on the grocery shelves. And this is in 2022, that this is happening, said Josephson. If you’re starting to see empty shelves at the grocery store, I think it’s the beginning of it, not the end of it. When you don’t have dairy and you don’t have eggs it doesn’t mean you’re going hungry. It just means you have to make different choices. I think that’s where we’re at now in Alaska; we have a lot of resources available to us, but it might not be what we’ve been used to.

Dear Reader: Are you hungry now?

References:

[1]Haines Highway from Haines Junction to Haines

[2]Alaska Division of Agriculture, Grants available to improve security of Alaska’s food supply, Press Release January 21, 2021.

[3]Alaska Fisheries Development Foundation

[4]Fishermen’s News; The Advocate for the Commercial Fisherman

[5]Feeding Alaskans; Man vs ADFG Machine

[6]Alaska Seafood Marketing Institute

https://www.alaskaseafood.org/about-asmi/

[7]ASME Seafood Recipes:

https://www.alaskaseafood.org/recipes/

[8]Kelp Farming in Alaska

Advertising is available on this website. I will write your story and it will gain continuous clicks through monthly display ads: Contact me at Donn@DonnListon.net

Lol, teacher, you are doing an Alaska food guide article. You also wrote about the local fishing economy and the environment to be developed. If you add some scenery and travel articles in it, I think it will be better, loud lol, I still prefer food