Where Is Public Education Going Now?

As a graduate of East Anchorage High School in 1969, I felt like one of the tiny fish raised in Alaska hatcheries and pumped through a four-inch hose into any of a number of Alaska lakes, to grow large enough to become opportunities for anglers to catch with reel and rod, after a good fight. Parting words from my teachers were “swim, little fish!”

Because my dad had come to Alaska as a telephone worker, he was a proud member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW 1547). As his son I would likely have qualified to enter the IBEW Electrical Apprenticeship Training School and ultimately joined the union cartel that assured members of great salary, benefits and retirement for the rest of their lives. As a high-paid tradesman, I might look down my nose at those posy-sniffing university elitists who took classes over a number of years and graduated into an ocean of unspecified opportunities.

But the summer after graduation I was adrift. The old man had kicked me out of the family home in Midtown Anchorage before I graduated, and I had built a camper on the back of a beat-up 1962 Chevy truck, where I lived to finish high school. I liked working with tools but I didn’t want to go into the trades for a career. I worked that summer in construction–mostly cleaning up job sites–and found myself in the employ of legislator Nick Begich, taking care of four kids while he and another high school teacher, Ivan Harrison, built apartments in East Anchorage. In the evenings–while Sen. Begich answered constituent mail–we talked about the future of Alaska.

This was a linchpin of my education.

With the Trans-Alaska Pipeline coming, it was all pie-in-the-sky. What would Alaskans do with all that money?

As a teacher, Nick saw bigtime education opportunities for future generations. As an eager learner myself, he encouraged me to seek higher education at the newly established Anchorage Community College (ACC) at Providence Drive and Lake Otis Parkway. The University of Alaska was in Fairbanks but this community college was finally in its own digs after years of holding night classes at West Anchorage High School. This was also the camel’s nose under the tent, to re-direct UA resources from a specialty university for Arctic living in Fairbanks to a something-for-everybody railbelt community college. Five concrete monoliths had been planted in a big mudhole across the street from Alaska Psychiatric Institute (API) for the benefit of Alaskans, like me. As far as I can tell UAA is still today mostly a glorified community college.

I wanted to swim in that pond.

Later, in the mid-1970s as a student and reporter for the Anchorage Daily News I became friends with the Superintendent of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Roy Peratrovich, who told me an amusing story reflecting the sentiment of many toward higher education:

A certain eager high school graduate from rural Alaska flew to Anchorage ready to start school. The taxi dropped him off at ACC. Because it seemed so unfinished the student ended up across the street at API walking around the grounds and wondering how to get in. Finally, a groundskeeper approaches the young man and asks if he can help him.

“I am new here and ready to get started on my education,” the young man said enthusiastically. “Is this Anchorage Community College?”

“Oh no,” replied the groundskeeper, “you have made a very serious mistake—this is Alaska Psychiatric Institution where they put crazy people!”

The young man, trying to make light of the situation, replied: “There isn’t really that much difference between the two, is there?”

“Yes, there is a lot of difference,” the solemn groundskeeper replied: “To get out of API you must show improvement!”

Roy issued a big belly-laugh with that story.

What about Alaska Higher Education?

Long story short, I took Begich’s advice and got a loan from the Alaska Commission on Postsecondary Education (ACPE) and began taking classes while working jobs to support myself. I didn’t follow in my father’s footsteps to become a blue collar soldier for the union and the Democratic Party. I had never trusted my teachers to be anything but poseurs, either, so I became a difficult student who always asked questions that couldn’t be answered, and took the path least traveled.

With so many opportunities all around, as the Trans-Alaska Pipeline was being built, I still resisted big money working construction while also giving up on ACC. I wanted more in my college experience, and Alaska Methodist University (AMU) was the underdog private college facing direct threat from the state’s revitalized UA

system in Anchorage. ACPE offered financing for attendance at the private school because the big fish entered a Consortium Agreement with AMU in exchange for its considerable library, so young Alaskans like me could get state loans to attend a noble but challenged private university.

I took classes not taught by State workers, and learned the value of looking at the origins of our language and the history of our nation, through an objective Alaskan academic lens. At the Daily News I even wrote stories about local churches for publication–and independent study Religion credit. Both AMU and the Daily

News benefited as I encountered learning on my terms. By the time I got my Bachelor Degree in 1974 I was a full reporter making monthly payments to ACPE for what I had borrowed.

This was a uniquely Alaskan education and I savored it. The true value of my training happened as I started my own business and made myself available to whatever career path God steered me onto. I am eternally grateful for this.

The Future of Higher Education is in School Today

Living on a sailboat in Juneau during the late 1980s, one day I had an epiphany about what I might pursue in my career at that time. Having generally a low opinion of the Alaska public education experience I had survived, I wondered: What if I tried to become the rare kind of inspiring teacher I had experienced on few occasions? Nick

had disappeared on an airplane traveling to Juneau from Anchorage October 16, 1972, but perhaps he was still nudging me at some level I could not know. So, I returned to the University of Alaska Southeast (UAS) to pursue teaching.

There I ultimately earned a Master’s Degree in Education in 1989.

This focused my life. Other Career events meant it took until age 52 to become a newly minted teacher. That’s when I discovered the University of Alaska program was producing relatively few of the thousands of teachers hired in 50+ Alaska School Districts. District administrators were mostly looking for young, cheap, easily fired teachers from Outside. I attended a Teacher Job Fair in Anchorage, with school board members and admin-istrators from all over the state. It was like a speed-dating event. They obviously didn’t want experience; they wanted compliance of newbie idealists who could regurgitate the meanings of certain educational buzzwords for treats.

I wasn’t a trained seal, but I found my way into Alaska’s Public Education Casino–with the few chips I had obtained at UAS–and played my luck upon gaining my Alaska teaching certificate in 2003, including one year teaching 6th Grade in Haines, Alaska, and later being nominated by my ABE students and selected in 2013 as a BP Teacher of Excellence.

Fast-forward to 2020: My experiences over 15 years as a working teacher bookmark the nearly 15 previous years of working for public sector teacher and state employee unions in Juneau. These are contrasting experiences. I always knew higher education was the key to getting into my kind of career pattern, and have given many students the advice Nick Begich gave me back in 1969: Borrow from ACPE for great rates to gain the education Alaska needs and you deserve.

Today I find myself in a new relationship to higher education as a commissioner on the ACPE, appointed by Gov. Mike Dunleavy in early 2020. I am one of 14 commissioners determining policy for providing loans to Alaskans seeking higher education or vocational training.

I had gotten to know Sen. Dunleavy when serving as an ABE instructor in his Wasilla Senate District.[1]

I aspired to elevate people who had failed in public education into meaningful careers so their own children would value education. I previously wrote two stories for publication about The State of Higher Education, which are now also on my blog.2

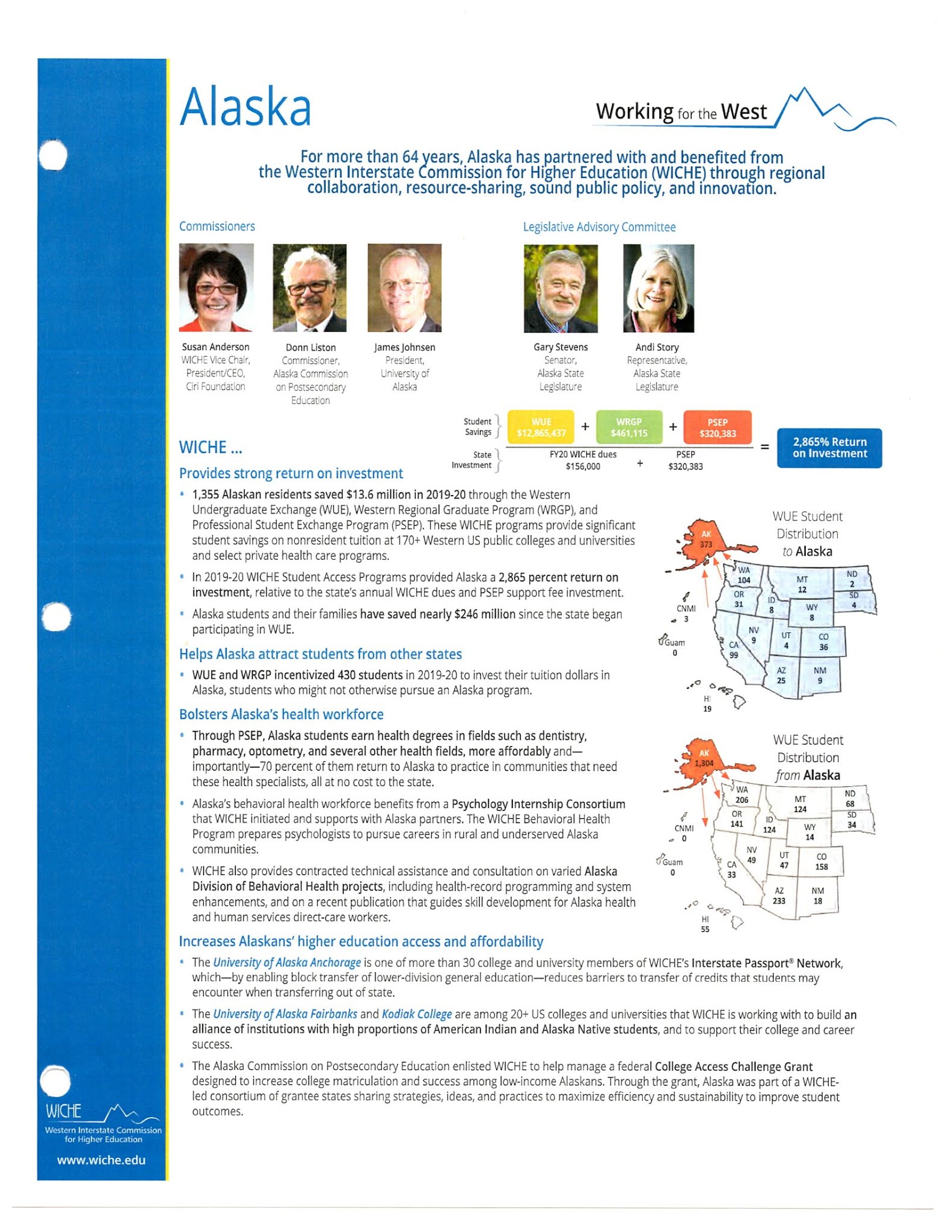

Additionally, Gov. Dunleavy also appointed me to the Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education (WICHE); another high honor. This commission includes three representatives appointed by each of the governors of 16 western states. I join two distinguished colleagues to pursue best opportunities for Alaskans seeking meaningful careers through interstate cooperation. The State of Alaska pays to be in this organization.[3]

Unfortunately when Alaskans take advantage of the opportunity to attend school at another institute for Alaska tuition rates, through the WICHE Interstate Agreement, they often do not return permanently.

WICHE Report: Knocking at the College Door, 2020[4]

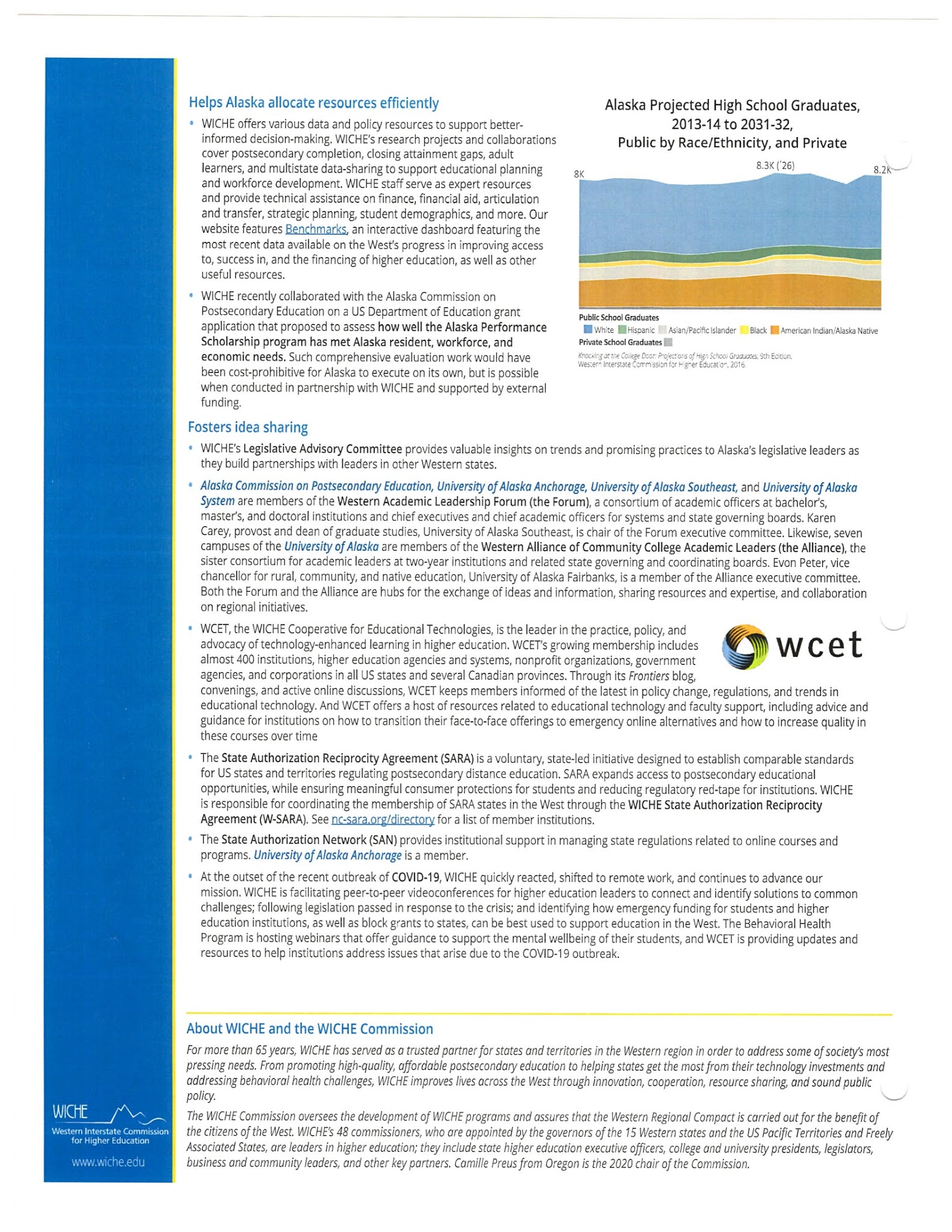

Every four years, WICHE publishes Knocking at the College Door, with detailed data and projections more than 15 years forward on high school graduate populations for all 50 states. With data disaggregated by state, gender, and ethnicity, WICHE’s national research on this topic is often considered, as the Boston Globe has termed it, “the industry gold standard.”

This is one of a number of research efforts performed by WICHE.

From this report:

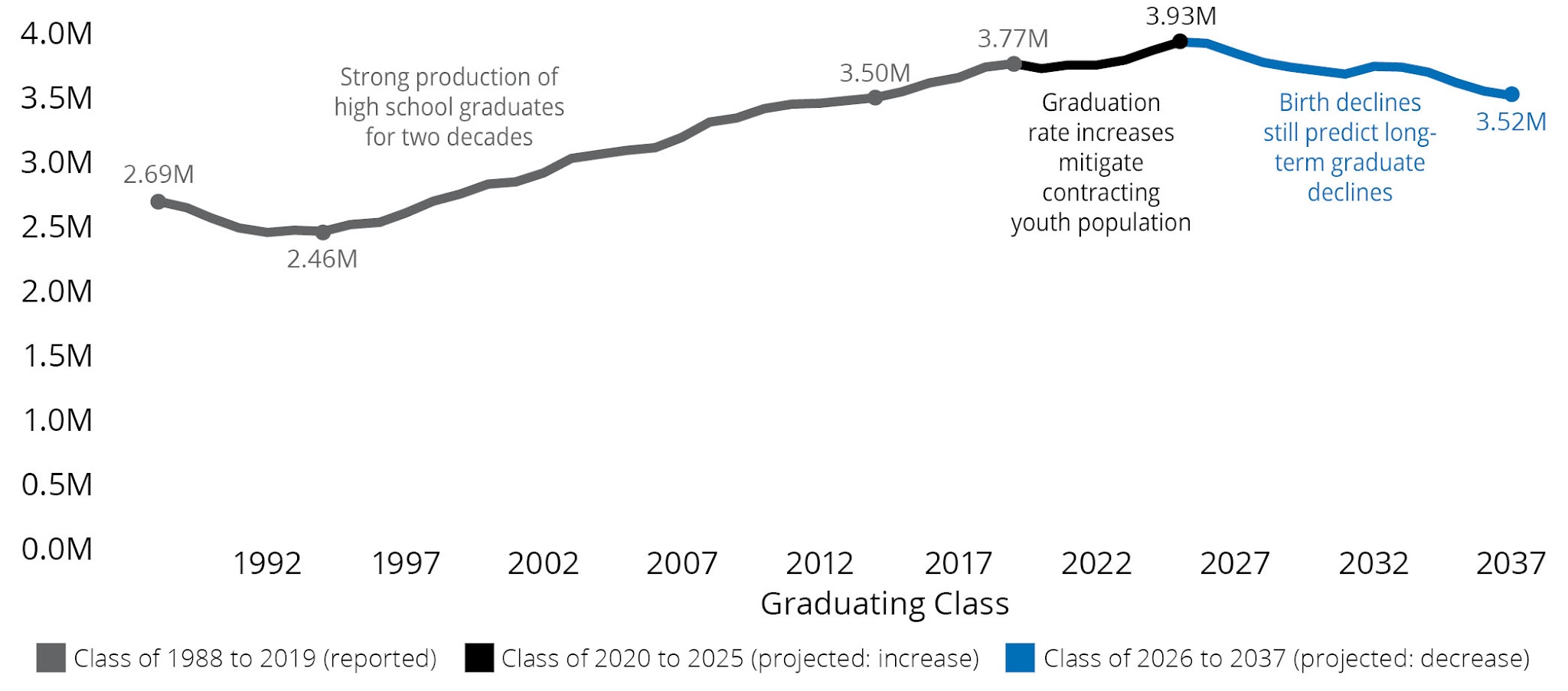

High School Graduate Trends—A Glimpse of the Future before COVID-19 Intervened Understanding the pipeline of high school graduates is crucial for a range of policymaking, economic development, and higher education planning needs across the county. WICHE’s 10th edition of Knocking at the College Door projects the numbers of high school graduates disaggregated by public and private schools and race and ethnicity out to 2037. The new projections show – generally speaking and with caveats about state and regional variation – slightly increased numbers compared to previous projections (now hitting a peak of just under four million graduates in 2025 compared to projections in the previous edition of just under 3.6 million).

Our anticipated glidepath.

State by state this report reflects on efforts by higher education institutions to provide the little fish out of our public education factories with information needed to survive in the lake, or even in the ocean. Alaska has one of the greatest high school dropout rates in the nation and many students from our high schools require remedial courses at UA before they can take 100-level coursework there.

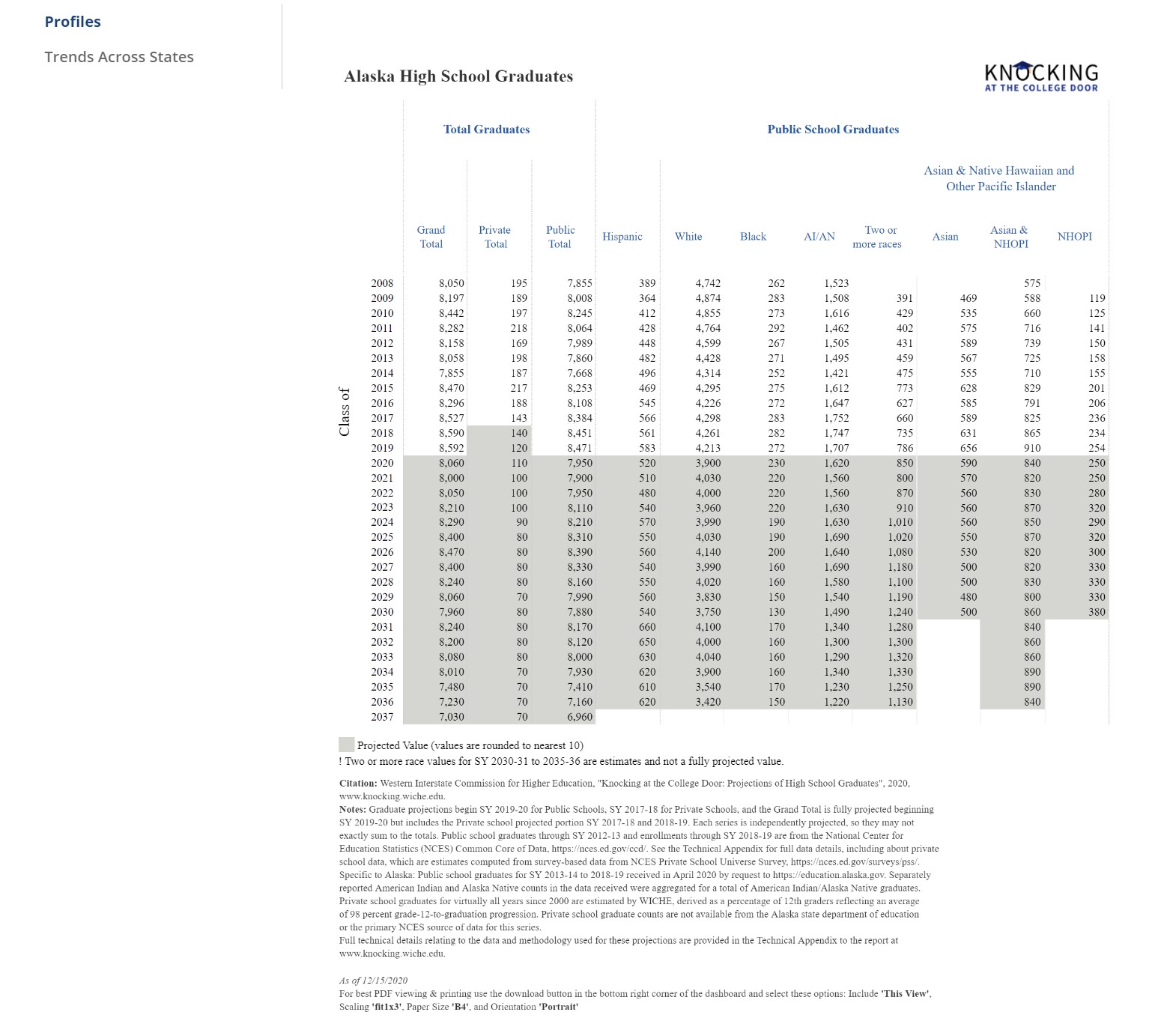

In 2019 Alaska graduated 7835 high school students, according to the Alaska Department of Education, while losing 1730 early leavers. In 1996 we had graduated 6301 in Alaska with 2199 high school dropouts. 1996 was coincidentally also the year the Alaska Legislature gave teachers the right to strike.[5]

From the national WICHE report: While the projections show a slightly improving picture for the number of high school graduates – due in great part to increases in high school graduation rates – they come with an enormous asterisk. Due to data availability, the numbers presented here represent actual enrollments and graduates from public schools through the Class of 2019, and from private schools through the Class of 2017, with the years from 2020 and forward being fully projected. Therefore, due to the timing and lack of available data, these projections do not capture any of the impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic, which is likely to have substantial long-term impacts on the education pipeline.

Figure 1 shows U.S. total annual high school graduates from the early 1990s through the Class of 2019 nationally, then continuing with this 10th edition projections through the Class of 2037. (This is the year through which WICHE can produce projections based on available data about recent U.S. births). According to the data WICHE collected from states, the U.S. produced 3.8 million high school graduates by the Class of 2019.* U.S. high school graduates are projected to peak in number at nearly 4 million (3.9 million) with the Class of 2025, potentially achieving 4 percent increase from current numbers.

*The U.S. total includes the 50 states and District of Columbia and covers the overwhelming majority of graduates from public high schools and the almost 10 percent of youth who attend private schools (nationally). Home-schooled or other pockets of youth

are not explicitly covered by the available data. WICHE provides an estimate of the number of graduates from Bureau of Indian Education schools at the national level in this edition, but it is not included here, because it is not available for all years. Projections for Puerto Rico are also available in the detailed data, but not included here.

These are projections of what might have been expected.

Alaska Education Projections

WICHE Research has established we are experiencing higher graduation rates since institution of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB) and subsequent federal programs since then. I question the caliber of that education in this state. The Alaska High School Graduation Qualifying Exams (HSGQE) required under NCLB were normed at 9th-10th grade and were given every year of high school in Alaska districts. Any student who could not pass this basic test was given a Certificate of Completion and opportunity to take the test on the two annual offerings available until they passed it to gain a district diploma. I personally provided instruction to

help many students pass that test.

Alaska teachers hated that test because obviously it also tested the teachers who passed students through the system without showing any of the expected improvement my friend, BIA Superintendent Peratrovich, had referenced in his story. The Alaska Legislature in 2016 passed a bill removing the requirement for a test of 9th-10th grade proficiency for Alaska students. Those who could not pass it were given their unearned diplomas retroactively.

This is part of Alaska’s Bigotry of Low Expectations legacy.

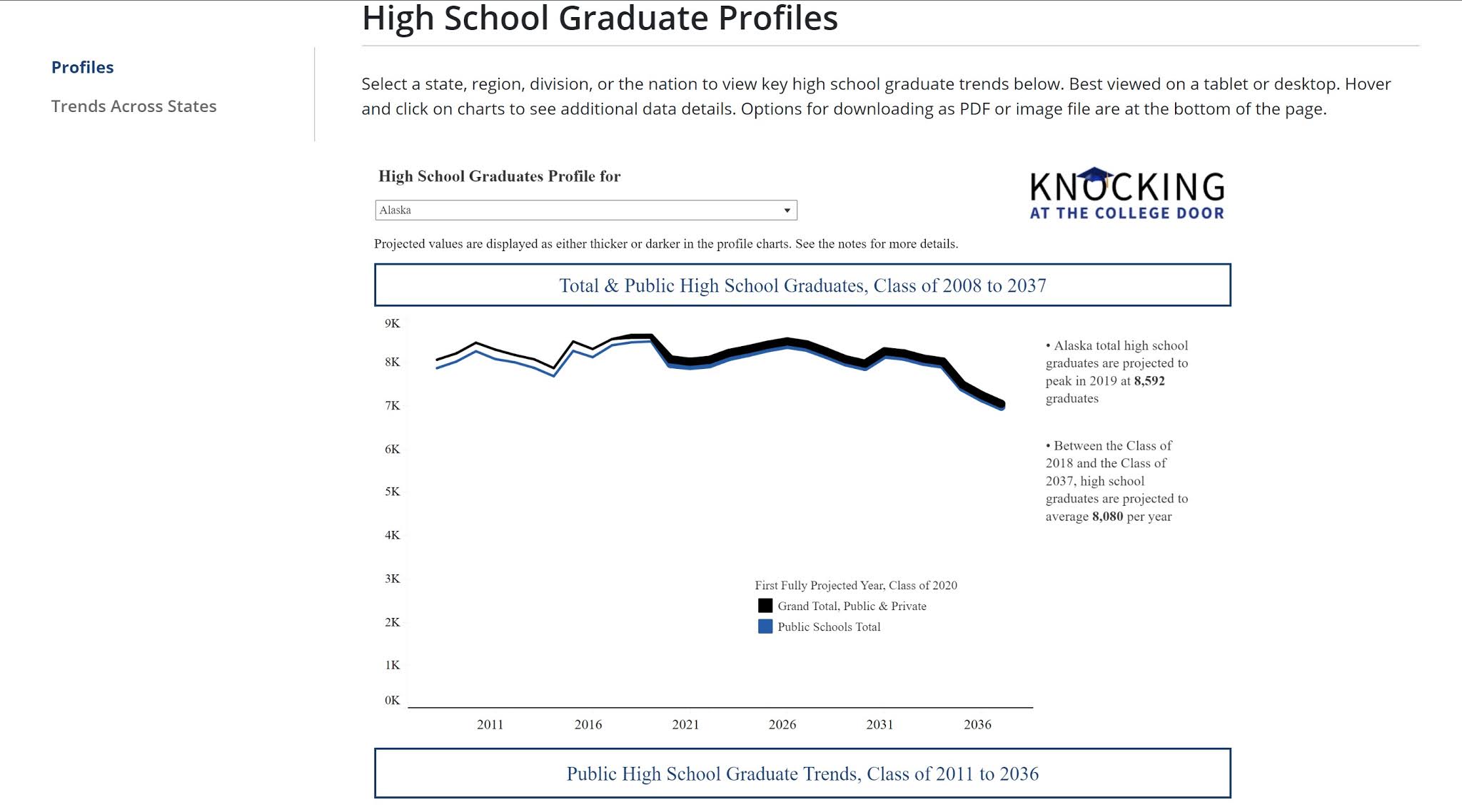

This table shows the WICHE research for Alaska students who might qualify to go to university or trade school in or out of Alaska.

Anyone having youth anticipating college can use another WICHE reference to determine how much individual colleges cost in the west: 2020 Tuition and Fees. https://www.wiche.edu/publications/

The more I learn about the nature of Alaska’s public education he more I am in wonder at it’s expanse. WICHE links our system to a network of other profound state systems in other western states. Today we do not now know what the China Pandemic will do to change these projected outcomes, but we do know all students must be encouraged to “Swim, little fish!”

References:

[1]Frontiersman: Basic education services expand for Valley adults

[2]The State of Higher Education

https://donnliston.net/2017/08/the-state-of-higher-education.html

https://donnliston.net/2018/12/the-state-of-higher-education-part-2.html

[3]Alaska

WICHE Profile

[4]Main Report: https://knocking.wiche.edu/report/

Executive Summary: https://knocking.wiche.edu/executive-summary/

Technical Appendix: https://knocking.wiche.edu/technical-appendix/

Dashboards: https://knocking.wiche.edu/dashboards/.

This page links to interactive data tables where you can see state-specific

information.

[5]AKDEED Data Center

https://education.alaska.gov/data-center

[6]National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data, “Dropouts, Completers and Graduation Rate Reports,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/pub_dropouts.asp.

National Center for Education Statistics, “Digest of Education Statistics,” accessed on December 3, 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/current_tables.asp